Van Gogh: Poets and Lovers at the National Gallery

14 September 2024 - 19 January 2025

Starry Night on the Rhone

On my first trip to the exhibition, a woman exhibiting her art at FRIEZE shared with me that the particular ochre in many of Van Gogh’s paintings in the exhibition was a new invention of his time. The thought thrilled me. Here was Van Gogh, like a gamer with the latest CPU, seizing this fresh pigment with childlike excitement and weaving it into his work. The ochre hums in his sunflowers, fields, and skies, connecting invention with artistry in a timeless and immediate way. Imagine the joy of discovery that must have coursed through him—an artist alive to the possibilities of his craft.

I was also struck by the deeply personal letters included throughout the exhibition, letters Van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo, his unwavering champion, and fellow artists like Gauguin. These letters offered windows into a man who, though tormented by mental illness, built his world on foundations of love and friendship. They revealed a period of his life where, despite the turmoil, connection and collaboration became his lifeblood. The sunflowers, painted specifically to brighten Gauguin’s room, radiate with this intention—a gesture of hospitality and a symbol of their fraught but significant bond.

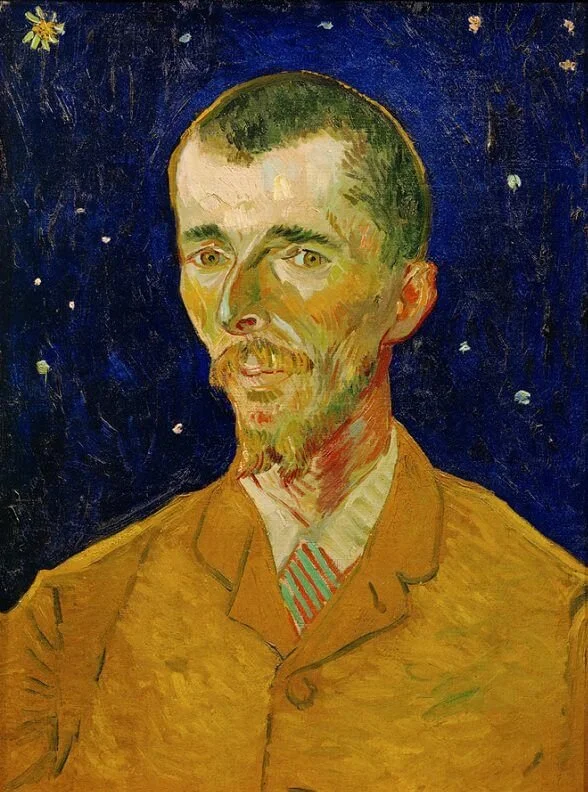

Similarly, the chair he painted for Gauguin, complete with symbolic items carefully chosen to represent him, speaks to Van Gogh’s ability to infuse the mundane with profound meaning. These moments are the epitome of art: the creation of beauty and the expression of care and humanity. One day, it was the starkness of the “Poet,” his head among a crowd of stars. Another was the quiet urgency of a lesser-known painting, originally a sketch tucked unassumingly into a corner, that had been transformed into a fully-fledged masterpiece. The progression from rough lines to vivid, layered colour seemed to echo Van Gogh’s journey— relentless refinement and ceaseless striving for connection. Van Gogh’s work is relentless in its longing, a ceaseless push toward connection—with nature, others, and himself. Experiences like these underscore the necessity of art in our lives, a reminder that beauty and humanity are intertwined in ways we are only beginning to understand.

The Poet

A docent told me about the final painting — it had hung upside down in the National Gallery for over 50 years. The butterflies, it turned out, worked both ways and what was meant to be an overstory of trees looked like a path when inverted. It took a five-year-old girl to notice something was wrong. Her observation led experts to confirm the error. This story of the upside-down butterflies feels emblematic of why we gather to see art in person: for the unexpected, the serendipitous, the moments that remind us of the collective act of looking and discovering.

Van Gogh: Poets and Lovers is not a passive experience. It confronts you, insists on your engagement, and rewards your attention with revelations long after you leave. This is why we need galleries to stand before these works and share their space. For the ochres that electrify. For the upside-down butterflies. For the stories that bind us to each other and the enduring, unrelenting pulse of art itself.